FDA: Solution to drug prices not as simple as clearing generic backlog

05 February 2016

A backlog of generic drug applications is not to blame for escalating drug prices that have become standard fare for presidential campaigns and congressional hearings over the past few months.

That's the gist of the testimony the FDA's Janet Woodcock gave Thursday in the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee's first oversight hearing of the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA). Instead, she fingered other market barriers that can dampen competition, including the market itself, dated manufacturing processes, risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) and the lack of bioequivalence measures for certain drugs.

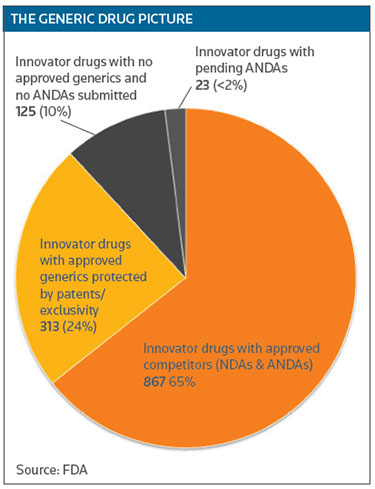

While generics have saved the country nearly $1.7 trillion from 2005-2014, that savings hasn't been evenly distributed, because the market for some indications is too small to encourage generic competition. Woodcock noted that 10 percent of the small-molecule drugs currently on the market have no generic competition, even though they are not protected by patents or exclusivity. Those are small-market drugs generally used to treat rare diseases. (See THE GENERIC DRUG PICTURE below.)

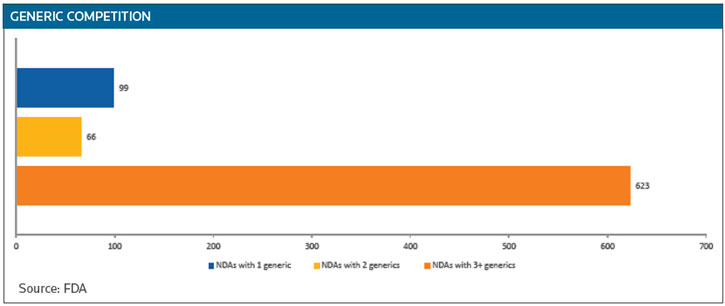

While 65 percent of innovator drugs do face competition, 99 have only one generic competitor and 66 have two. The big price reductions generated by generics occur when there are three or more competitors, Woodcock said. (See GENERIC COMPETITION below.)

The most talked-about price hikes this past year occurred when a company bought an older drug with no competition and then hiked the price. In some of those instances, the market wasn't big enough or lucrative enough to encourage generic development.

NOT A 'FLIP OF A SWITCH'

Woodcock pointed out that it takes time to develop a generic. It's not a matter of "flipping a switch" and submitting an application to the FDA when a price spike in a sole source drug hits the market. However, the agency is encouraging industry to adopt advanced manufacturing processes that would shorten start-up and production times.

While food and other industries use automated, continuous manufacturing processes, drugs are still produced as if they're being "cooked" – one batch at a time, Woodcock said. Using advanced manufacturing in the biopharma industry would create more agility, she added.

Her words will be welcomed by companies pushing for adoption of new manufacturing technologies to speed time to market and reduce costs. In the past, the biopharma industry has been conservative in investing in new manufacturing platforms because of the significant costs involved, the high price of delays and unexpected setbacks, and the time needed to implement new technology. Some of industry's concerns centered on whether switching to new manufacturing processes would delay or disrupt FDA approval, which could prove costly. (See BioWorld Today, Oct. 30, 2015.)

Although the FDA doesn't consider pricing in its review process, it does expedite first-generic applications, as well as those that could alleviate a potential shortage, Woodcock said. She assured the senators that the current backlog contains no first-generic applications that would address the recent price hikes of drugs like Turing Pharmaceuticals AG's Daraprim (pyrimethamine).

While it can expedite first generics, the agency doesn't fast track generic applications in response to price spikes. Since it hasn't been defined, "we don't know what a price spike is," Woodcock said. Where would the line be drawn? When the cost of a pill goes from 10 cents to 20 cents? The FDA staff is made up of doctors and scientists, she added, not economists and financial experts.

UNINTENTIONAL BARRIER

Congress itself created an unintentional barrier to competition when it called for a shared REMS program for some innovators and their generics as part of the FDA Amendments Act (FDAAA). "This has proven . . . very challenging for the FDA to get this done," Woodcock said, as it is difficult to get companies to share a REMS when they are competing for part of the innovator's market.

Intended to lighten the burden for health care providers and patients who might be switched from the innovator to a generic, the idea of a shared REMS has raised questions of fairness, especially when the innovator is the one that footed the time and money to develop a complex safety program that may involve patented components, databases or registries. And once a shared REMS is in place, the question remains of who bears the cost of amending, maintaining and assessing it. (See BioWorld Today, Sept. 23, 2014.)

The shared REMS requirement often blocks or delays competition, Woodcock said, as the agency, by law, has to try to negotiate the strategy. After failing to do so, it can settle for two REMS – the one the innovator follows and a second, separate-but-equal, strategy followed by all the competitors. If the FDA could skip the negotiation process and go straight to a separate REMS, the generics could be launched earlier.

REMS form another barrier to competition when they are used to deny access to the innovator drug for generic R&D purposes. "More broadly though, the companies on their own behalf have restricted programs that we don't fully understand, but they aren't related to REMS," Woodcock said. Like REMS, such programs that restrict access through specialty pharmacies are used to keep generic companies from developing copies of the innovator.

The FDA has received more than 100 inquiries from generic companies about access problems, Woodcock testified. The agency has done everything it can to respond, including sending letters to the innovator and referring them to the FTC.

Innovators believe it is their duty to their stockholders to delay competition as long as possible, Woodcock said, adding that REMS, like citizen petitions, have become yet another way to do that.

NEED FOR RESEARCH

Another barrier Woodcock mentioned is a gap in the science. The FDA has issued nearly 50 drug-specific guidelines on bioequivalence testing for generics, but no convincing bioequivalence test method has been discovered for some complex drugs, she explained. In lieu of such a test, generics have to be evaluated in clinical studies, which increases their cost and time of development.

To fill that gap, especially for drugs that are not systemically absorbable, the FDA needs research dollars, as that is an area that the NIH doesn't address. To date, GDUFA has funded $34.9 million in research programs to open up those pathways. But scientific research takes time, Woodcock said.

As for the generic backlog itself, Woodcock said the FDA is on target to work through all the applications by time GDUFA II comes on board. New generic applications are getting a 15-month review window. Beginning in October, that window will be shortened to 10 months.

Woodcock blamed the backlog on the FDA's past inability to keep up with the significant growth and globalization of the generics market. Since GDUFA was passed in 2012, the agency has used the new user fees to beef up its staff and hire about 70 new investigators to help with foreign drug inspections.

PrintOur news

-

14 March 2024

-

26 February 2024

-

NovaMedica team wishes you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!

26 December 2023

Media Center

-

Research calls for greater investment in Alzheimer’s clinical trials

03 May 2024

-

Stress impact on protein particle formation for monoclonal antibody formulation

03 May 2024

-

Health Ministry registered Russian drug for ankylosing spondylitis

02 May 2024

-

Production of finished drugs in Russia grew by 13.8%

02 May 2024