PAPs valuable but increasingly ensnared in drug pricing predicament

21 October 2016

"If you can't afford your medicine, Astrazeneca may be able to help."

Millions of U.S. consumers hear and read those words every day in direct-to-consumer (DTC) ads from the London-based pharma and similar verbiage from its cohorts. Copay assistance, discounted pricing and free medications for those who qualify are hallmarks of the biopharma industry's ubiquitous patient assistance programs (PAPs), which also encompass services such as insurance reimbursement support, counseling, genetic testing, health care classes and certain devices.

PAPs – some created decades ago – were established to provide a safety net for patients with the greatest financial need to ensure they could have access to life-saving medications. That sense of compassion still undergirds the efforts of many programs.

"There is always going to be a need for patient assistance programs because there will always be gaps," Gary Pelletier, executive director of the Pfizer Patient Assistance Foundation, told BioWorld Today. "We're never going to have a perfect state where everyone has perfect coverage."

Even if all patients had optimal prescription drug coverage providing $5 copays on every prescription drug, "some patients will still need help because they might be on multiple medicines, and $5 across multiple medicines can add up," Pelletier pointed out. "We do have many patients in our program who have very low incomes. Even a $5 copay, if they're lucky enough to have that, can be too much."

But in recent years PAPs also have become vehicles for certain bad actors to increase prices and further muddle the enormously complex pricing of drugs across the supply chain. In February, Democratic members of the House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform issued a blistering memo alleging that officials at Valeant Pharmaceuticals International Inc. used the company's PAPs to justify raising prices and to generate higher revenues by driving patients into a closed distribution system. The committee concluded, based on a review of 75,000 pages of internal company documents, that Valeant used its PAPs to divert attention from price increases, especially for drugs it sought to categorize as orphan products.

The committee's findings were part of a string of revelations about Valeant business practices that led to the ouster of CEO J. Michael Pearson. (See BioWorld Today, March 22, 2016.)

'IF WE DID AWAY WITH THEM, IT WOULD HURT PATIENTS'

Although the actions of a few have shone a harsh light on PAPs, they've also fueled debate over a larger question: Are these programs part of the industry's drug pricing problem or part of the solution? The concerns have reached beyond the halls of Congress. This month, Annals of Internal Medicine published several commentaries on the topic, with one suggesting that copay assistance – the bedrock of most PAPs – may do more harm than good to the U.S. health care system. Health policy researchers Peter Ubel, of Duke University, and Peter Bach, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, suggested that the PAP hastily introduced by Mylan NV to deflect attention from the soaring price of its Epipen represented "a recipe for higher health care costs in the future."

The Epipen debacle, which became the subject of water cooler chatter and late night TV talk show monologues for more than a month, was largely responsible for dragging PAPs into the larger controversy surrounding drug pricing. (See BioWorld Today, Aug. 24, 2016, Aug. 26, 2016, and Aug. 30, 2016.)

Ubel and Bach argued that co-pay assistance programs, in general, diminish price pressure, undermine benefit designs that allow for low-cost insurance plans, reduce negotiating leverage for insurers and prevent patients from acting as consumers.

The researchers pointed out that the copay assistance programs that serve as the centerpiece of most PAPs "are not as good as they seem," maintaining that biopharmas offer such assistance "only for those that patients fill before their insurance kicks in. When patients reach their out-of-pocket maximums, insurers pay all future costs. Because insurers cannot distinguish between payments from patients and copay coupons, the coupons can be used to speed patients to their out-of-pocket maximum even when they have not paid the share their insurance plan requires."

Ubel and Bach don't advocate eliminating copay assistance programs altogether because, "if we did away with them, it would hurt patients." Ubel told BioWorld Today. He added, however, "if we rely on copay assistance, it just drives prices up in the long run."

PAPs have critics even within the industry. Kalobios Pharmaceuticals Inc. CEO Cameron Durrant, who was the first to issue a responsible pricing model for his company – for now a paper tiger, since Kalobios has no commercial products – said it's important to step back and consider the reason the industry uses coupons and other discount programs.

"People are feeling the pinch of higher out-of-pocket costs," he acknowledged, "but why is that? Generally, it's because of the formulary position of their therapies and the direct relationship to the price of their drugs."

Durrant questioned whether PAPs benefit the patients who need the most help, maintaining that the programs are structured more to meet commercial sales targets than patient needs, with actual coupon and discount card redemption rates hovering in the single digits.

Coupons and savings cards also represent an extra burden on pharmacies, especially in small communities that are underserved by the national chains, according to the National Community Pharmacists Association (NCPA). Most cards involve billing as secondary insurance, adding to the pharmacy's work flow. On top of that, the cards often are handed to patients by prescribers without explanation, leaving pharmacists with the responsibility of educating customers about eligibility and usage.

To Durrant, the obvious solution is to move away from discount mechanisms toward pricing models that are fair, transparent and sustainable.

"Patient assistance programs are a sign of the broader malaise around price," Durrant told BioWorld Today. "They're an effort to tackle pricing through the back door. If we don't take this issue on, it's going to be done to us as an industry through regulation."

COUPON USE EMPLOYED AS NEGOTIATING TOOL

Most biopharmas – especially large, multiproduct companies – don't buy that line of thinking. They argue that PAPs are used legitimately to track demand for certain medications – especially at launch, when companies work closely with their PAPs to make coupons and other discounts widely available. In addition to mitigating patient out-of-pocket costs, biopharmas use the programs to generate evidence of demand for newly approved therapies. Coupon use is employed as a negotiating tool with pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to argue for a drug's inclusion in their formularies – preferably in a favorable tier with low copays, where therapies are more accessible to patients.

Over the years the leverage in those discussions has tilted away from the pharma industry. The nation's largest PBMs – which are operated by mega pharmacy chains such as CVS (Caremark) and Rite Aid (Envisionrx) or, like Express Scripts, control their own specialty pharmacy subsidiaries (Accredo and Lynnfield Drug) – often drag their feet on formulary decisions. Higher drug costs generate higher rebates from drug manufacturers as a percentage of list price, and PBMs are not obligated to pass those savings along to patients.

The three largest PBMs control about 80 percent of the middle ground in the U.S. drug pricing supply chain, or approximately 180 million covered lives. Increasingly, PBMs use that clout to exclude drugs from their formularies. CVS excluded 124 drugs this year, a 63 percent increase over the number of drugs it excluded in 2014, according to a report by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, while Express Scripts excluded 80 drugs in 2016, up 67 percent from two years ago. (See BioWorld Today, May 13, 2016.)

PBMs also exert their power over independent community pharmacies that operate mainly in rural and small communities by imposing direct and indirect remuneration (DIR) fees at the point of dispensing and copay clawback fees negotiated into their contracts with payers. DIR fees – essentially "pay to play" payments to participate in a preferred pharmacy network – originally were associated with the Medicare Part D program. But earlier this year, 57 percent of community pharmacists surveyed by the NCPA said they now see those fees in commercial plans, and 87 percent of respondents indicated the fees significantly affected their ability to provide patient care and remain in business.

Clawbacks – obligations imposed on pharmacies to collect escalated copay amounts with the difference pocketed by the PBM – also inflate copays, most often in high-deductible prescription drug plans where the patient bears the entire cost, according to the NCPA. Patients rarely realize they're paying a higher copay than the negotiated rate, let alone that the extra dollars go back to the PBM rather than to the local pharmacy. More than four of five community pharmacists told the NCPA they witnessed copay clawbacks at least 10 times during the month prior to its survey.

Earlier this month, a lawsuit filed in Minnesota similarly charged Unitedhealth Group Inc. of overcharging customers by setting up a clawback system that forced members to pay two to three times or more what the drug cost the insurer. That lawsuit is seeking class-action status on behalf of thousands of insured customers across multiple states.

'PATIENT ASSISTANCE IS HERE TO STAY'

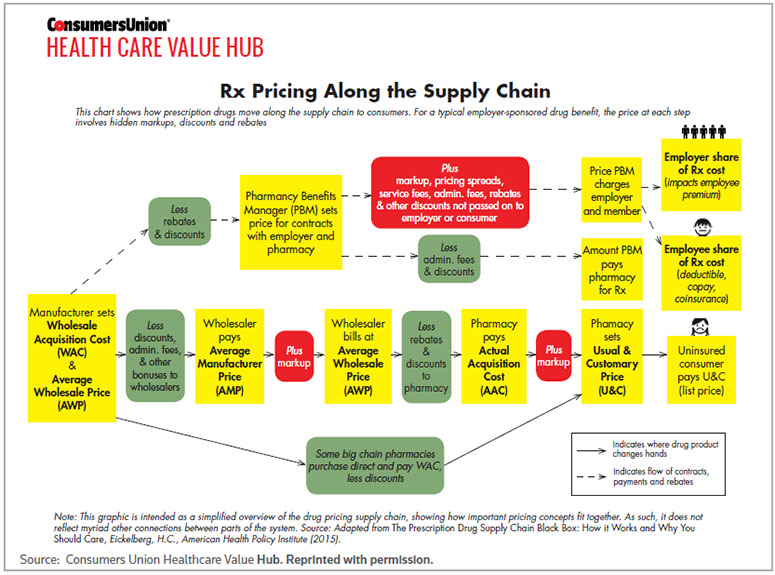

The complexity of drug pricing across the supply chain has stirred the waters on the role of PAPs despite the fact that those programs exist outside drug formularies. A simplified flow chart developed by the Consumers Union Health Care Value Hub (see chart below) offers a telling illustration of the numerous handoffs and mark-ups that occur between drug manufacturers and patients, whether insured or not. The cost to operate PAPs is typically factored into the wholesale acquisition cost and average wholesale price at the front end of the supply chain, but those programs don't add value until patients access them at the end of the line.

Caroline Pearson, senior vice president of consulting firm Avalere Health, said PAPs offer "a real backstop" to uninsured and commercially insured patients, alike.

"Patient assistance programs are well-entrenched and likely to remain a big part of the health care system until we're at a point where there's universal insurance and cost-sharing is affordable for patients," Pearson said. Given that "we're heading toward higher out-of-pocket burden for patients, not lower, patient assistance is here to stay."

But how well do PAPs work, particularly to help patients with the greatest financial need?

In short, that's hard to say. Every major biopharma and many smaller companies sponsor PAPs, either in-house or through the assistance of third parties. Some large drug manufacturers maintain that they've plowed tens of millions of dollars into those programs. Few would dispute that the industry, in the aggregate, has spent hundreds of millions of dollars to support internal PAPs and those operated by not-for-profits and patient advocacy organizations.

For the most part, patients can easily navigate to PAPs on drug company websites. Some, like Pfizer's RxPathways, provide patients with detailed information about drugs that are part of a copay assistance and/or deeply discounted pricing program as well as participating pharmacies and other tools and resources before asking them to click on a link for additional assistance or to download an application. Once that process begins, patients typically are asked to submit income information in the form of a federal tax return, W-2 form, recent pay stub, Social Security or related retirement income or dividend and interest statements. Some PAPs are less forthcoming before asking patients to submit the same income information.

Although some patients are reticent to provide such data, the overwhelming majority express gratitude for whatever assistance they receive from the PAP toward the out-of-pocket cost of their medicines, according to Pfizer's Pelletier.

But some of the neediest patients – including those who receive drug benefits through Medicare, Medicaid and some other federal programs – are prohibited by federal law from using coupons and other prescription drug savings programs. Biopharmas may choose to make medicines available to those patients at no cost through a PAP or third party, but giveaways are difficult to manage for all but the largest companies that can spread the outlays across multiproduct platforms.

And, while income-based programs generally are available to any patient who meets the financial criteria, the use of copay coupons is more closely aligned with brand name drugs that face competition from a lower-cost therapeutic equivalent. That distinction in PAPs is a problem, according to Lynn Quincy, director of the Consumers Union Health Care Value Hub.

"[Coupons] are very targeted, they're not broadly available and they're totally part of the marketing and sales strategy of the company," Quincy told BioWorld Today. "The way we think about this is that consumers pay, at the end of the day, either through their premiums – sharing the cost of the benefit design created by their insurer – or through their cost-sharing, or copay. They're often not benefited when the coupon fills in their cost-sharing because it means we've leveraged a high insurance payment for an expensive drug that, in many cases, has a therapeutic equivalent."

PBMS 'WRITE THE RULES OF THE ROAD'

A better way to help patients, Quincy said, is to reduce the cost of drug development and simplify the supply chain. She cited PBMs as a major stumbling block in efforts to accomplish the latter.

"Pharmacy benefit managers really write the rules of the road along that supply chain," Quincy said, "and they typically don't even have a fiduciary obligation to the employer at the other end of the chain. PBMs were formed to keep costs down by bringing the power of a large patient base and negotiating with drug manufacturers to get better prices for insurers. Instead, they've amassed all that power for themselves. They've introduced incredibly complicated pricing schemes, and nobody can really unravel the final price of the drug."

Indeed, biopharmas maintain that they don't know the price that any given patient pays for a drug at the point of dispensing unless they offer a flat-fee coupon through their PAP. Mike Narachi, CEO of Orexigen Therapeutics Inc., which markets the single product, Contrave (naltrexone and bupropion), in the U.S., offered an example. The obesity drug has a retail price of $220 for a month's supply, and pharmacy mark-ups typically push that price to about $245 in the retail channel. The company pays additional fees to third-party logistics firms, wholesalers and PBMs.

Orexigen has so far eschewed mail order distribution so it doesn't contend with those additional fees. Still, between the time the product leaves the company's manufacturing facility and the time it is picked up by the patient at a local pharmacy, a dizzying cycle of handoffs has layered on the costs.

At a high level, Orexigen knows that approximately 70 percent of Contrave patients pay out of pocket. But at the point of dispensing, the company doesn't know whether an individual patient is paying the full retail cost or has insurance coverage and, if so, the amount of the copay or whether the deductible has been met. The company also doesn't know whether or to what extent rebates paid to the PBM by Orexigen were passed on to the consumer. Coupons and savings cards, he said, represent a mechanism to offer a predictable price to patients in the face of fees that drug manufacturers can't control.

"What we're seeing – which, to me, is one of the most disturbing trends – is the vertical integration of insurers, pharmacies and PBMs," Narachi told BioWorld Today. "Competition can come in and squeeze out inefficiency when there's transparency. When there's no transparency, coupled with a high degree of market power, you don't get that competition."

PBMs actually may influence whether or to what extent patients access copay assistance and other discounts under PAPs, according to Ronna Hauser, the NCPA's head of regulatory affairs. Some third-party contracts stipulate that pharmacies can't accept savings cards because they interfere with the formulary structure established by the PBM or the copay incentives designed by the plan, she said. In other cases, coupons and savings cards are used to offset different levels of cost in tiered formularies, limiting the amount of assistance based on the copay level.

'IN THE END, EVERYBODY IS CONFUSED'

Although PAPs may appear to be victims more than perpetrators of the current drug pricing debate, biopharmas haven't exactly helped their cause. Critics charge that the programs operate as black boxes in much the same way as the pricing of drugs across the supply chain. The methodology behind most PAPs – which drugs are placed into the programs and why, how often and why therapies are removed, what frustrations patients encounter in seeking to qualify for the programs and how companies modify their PAPs to respond to market pressures – is hidden behind a wall of silence. BioWorld contacted nearly two dozen biopharmas that promote their PAPs, either on websites or in DTC ads. Many – including Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc., Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Amgen Inc., Biogen Inc., Celgene Corp., Gilead Sciences Inc., Glaxosmithkline plc, Sarepta Therapeutics Inc. and Shire plc – declined to discuss their programs, in some cases after voicing initial enthusiasm about the opportunity. Others – including Astrazeneca and Allergan plc, where CEO Brent Saunders also has advocated responsible drug pricing – did not respond to interview requests.

Paul Hastings, president and CEO of Oncomed Pharmaceuticals Inc., of Redwood City, Calif., and vice chairman of the Biotechnology Innovation Organization's board, where he chairs the patient advocacy committee, is sympathetic to that reticence. PAPs were adopted by drug manufacturers on a wholesale basis to help insulate patients from the vagaries of drug pricing, he said, and those good intentions have been twisted in the outcry over drug prices.

"Drug coupons or cards were designed by our industry to help patients deal with the astronomical increases in their copays," Hastings told BioWorld Today. He attributed those increases not just to the actual cost to develop drugs but also to the inclination by PBMs to pocket rebates from drug manufacturers, resulting in higher insurance premiums and copays.

"In the end, everybody is confused," Hastings said.

Express Scripts, the nation's largest PBM, and America's Health Insurance Plans, the health insurance industry's trade organization, did not respond to interview requests about their role in the process.

Biopharmas are willing to develop constructive solutions to address the drug pricing conundrum and the role that PAPs should play, according to Hastings, who also pleaded for greater cooperation during an Allicense 2016 session at the BIO International Convention. (See BioWorld Today, June 9, 2016.)

"But let's make sure the questions we're asked are questions we can answer," he insisted. "We need to get everyone in the room together, and we all need to have the courage to explain how we do what we do. This is a problem for everybody, so let's fix it."

PrintOur news

-

14 March 2024

-

26 February 2024

-

NovaMedica team wishes you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!

26 December 2023

Media Center

-

Big Pharma’s ROI for drug R&D saw 'welcome' rebound in 2023: report

25 April 2024

-

Orphan drug market to reach $270B by 2028 : Evaluate

25 April 2024

-

Russian drug for the treatment of viral hepatitis will be exempt from duty in Mongolia

24 April 2024

-

PM Mishustin: “We need to increase the production of vital and essential drugs in Russia”

24 April 2024